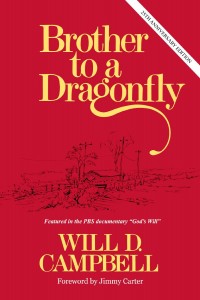

A truly original character died this week. I first got to know Will Campbell through his splendid book Brother to a Dragonfly. Typical of Will, he shone the spotlight not on his own story but rather on that of his alcoholic, self-destructive brother Joe.

A truly original character died this week. I first got to know Will Campbell through his splendid book Brother to a Dragonfly. Typical of Will, he shone the spotlight not on his own story but rather on that of his alcoholic, self-destructive brother Joe.

Ordained as a teenager, Will was destined to be a preacher. No one could have predicted, though, that he would choose for his flock first the leaders of the civil rights movement and then later a motley assortment of rednecks and Ku Klux Klansmen.

Preacher Will knew the civil rights luminaries intimately and became known as their chaplain. His own credentials were impeccable. The University of Mississippi had fired him from his post as director of religious life after he was seen playing ping pong with a black man. He endured many other indignities and threats of violence as he marched and protested and lobbied for justice. He joined Martin Luther King Jr. at the founding of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and months later helped escort nine black

students through angry mobs in Little Rock, Arkansas. He was the lone white man to join the mourners at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis hours after King’s assassination.

Yet, as Campbell finally concluded, “If you’re gonna love one, you’ve got to love ’em all.” Ultimately he realized that he was associating mainly with white liberals who saw the world just as he did. In those days, lots of people cared about oppressed minorities in the South—hence the marches, sit-ins, and court challenges. Who cared about the white rednecks?

A confrontation with his agnostic friend P.D. East brought this fact home to Campbell. East, a character in his own right, had communist leanings and published a paper outspoken on integration, neither stance endearing him to his Mississippi neighbors (death threats later chased him out of the state). Campbell, though, was one Christian whom East respected. “In ten words or less, what’s the Christian message?” East once challenged him.

We were going someplace, or coming back from someplace when he said, “Let me have it. Ten words.” I said, “We’re all bastards but God loves us anyway.” He didn’t comment on what he thought about the summary except to say, after he had counted the number of words on his fingers, “I gave you a ten word limit. If you want to try again you have two words left.” I didn’t try again but he often reminded me of what I had said that day.

I once repeated that story while speaking at Willow Creek Community Church in Chicago, and some irate listeners missed the point entirely, objecting to the word bastards. Actually, Campbell chose the word for its theological accuracy: spiritually we are illegitimate children, invited despite our paternity to join God’s family. The more Campbell thought about his impromptu definition of the gospel, the more he liked it.

Later, P. D. East put that definition to a ruthless test, on a day when an Alabama sheriff gunned down one of Campbell’s friends, a student from Harvard Divinity School.

“Let’s see if your definition of the Faith can stand the test,” East taunted the grieving Reverend Will. Did God love the gentle young man who had come south to lend his help to the civil rights cause? Of course. What about the redneck sheriff who murdered him in cold blood—did God love him? Campbell had to admit that, yes, God loved him too. Then came the final question, one that stabbed like an arrow to the heart: “Which one of these two bastards do you think God loves the most?”

At that moment, Will Campbell came face to face with the scandal of grace. He wrote:

Suddenly everything became clear. Everything. It was a revelation. The glow of the malt which we were well into by then seemed to illuminate and intensify it. I walked across the room and opened the blind, staring directly into the glare of the street light. And I began to whimper. But the crying was interspersed with laughter. It was a strange experience. I remember trying to sort out the sadness and the joy. Just what I was crying for and what I was laughing for. Then this too became clear.

I was laughing at myself, at twenty years of a ministry which had become, without my realizing it, a ministry of liberal sophistication….

I agreed that the notion that a man could go to a store where a group of unarmed human beings are drinking soda pop and eating moon pies, fire a shotgun blast at one of them, tearing his lungs and heart and bowels from his body, turn on another and send lead pellets ripping through his flesh and bones, and that God would set him free is almost more than I could stand. But unless that is precisely the case then there is no Gospel, there is no Good News. Unless that is the truth we have only bad news, we are back with law alone.

What Will Campbell learned that night was that grace extends not just to the undeserving, but to those who in fact deserve the opposite: to Ku Klux Klansmen as well as Black Panthers. His views on justice certainly did not change, and he kept agitating for it, side-by-side with the marchers. Yet he also became known as “an apostle to the rednecks.”

He explained, “I have seen and known the resentment of the racist, his hostility, his frustration, his need for someone upon whom to lay blame and to punish…With the same love that it is commanded to shower upon the innocent victim of his frustration and hostility, the church must love the racist.”

He explained, “I have seen and known the resentment of the racist, his hostility, his frustration, his need for someone upon whom to lay blame and to punish…With the same love that it is commanded to shower upon the innocent victim of his frustration and hostility, the church must love the racist.”

Campbell bought a farm outside of Nashville, and began to befriend some of the best names in Country Music as well as notorious racists and Klansmen. For years he sat on his front porch smoking a corncob pipe and drinking a homemade brew of who-knows-what while expounding the gospel of grace. He would grind his own cornmeal at a gristmill out back.

After Campbell pulled himself out of the limelight, he seemed to become more famous than ever. People like Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson, Tom T. Hall, Dick Gregory, Jules Feiffer, and Studs Terkel sought him out. President Jimmy Carter spoke of him with appreciation. Doug Marlette’s syndicated comic strip, “Kudzu,” used him as the model for the Rev. Will B. Dunn, complete with a broad-brimmed clerical hat.

After Campbell pulled himself out of the limelight, he seemed to become more famous than ever. People like Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson, Tom T. Hall, Dick Gregory, Jules Feiffer, and Studs Terkel sought him out. President Jimmy Carter spoke of him with appreciation. Doug Marlette’s syndicated comic strip, “Kudzu,” used him as the model for the Rev. Will B. Dunn, complete with a broad-brimmed clerical hat.

The rocking chair on his front porch stopped rocking a couple of years ago when Campbell suffered a stroke. And now the renegade preacher has fallen silent at the age of 88, leaving behind his wife of 67 years.

Thank you, Preacher Will, for letting the scandal of grace turn your world upside down, and then setting loose the message among the rest of us who badly need it. The world doesn’t consist of layers of “good people” and “bad people.” You got it right: We’re all bastards, but God loves us anyway. May we never forget either part of that formula.

Leave a Comment