In November I traveled to Grand Rapids, Michigan, to film a portion of a video curriculum on Mere Christianity, by C. S. Lewis. It’s the first such curriculum authorized by the Lewis estate, and is hosted by Eric Metaxas. I felt honored to be asked to contribute to the project.

In November I traveled to Grand Rapids, Michigan, to film a portion of a video curriculum on Mere Christianity, by C. S. Lewis. It’s the first such curriculum authorized by the Lewis estate, and is hosted by Eric Metaxas. I felt honored to be asked to contribute to the project.

I bought my paperback copy of Mere Christianity in 1968, almost fifty years ago. (Brand new it cost me $1.25!) It’s a measure of C. S. Lewis’s greatness that he could tackle some of the thorniest issues we’ll ever encounter, and carve a path through them in a way that still guides us decades later.

The story of C. S. Lewis has been told many times. A convinced atheist who found his lack of faith challenged by friends like J. R. R. Tolkien and Charles Williams. A scholarly specialist in medieval literature who became best known as a writer of the Narnia books for children. A confirmed bachelor who married a Jewish divorcée from Brooklyn at the age of 58, mainly to allow her to stay in England, only to fall in love and have four sweet years together before she died of cancer.

The story of C. S. Lewis has been told many times. A convinced atheist who found his lack of faith challenged by friends like J. R. R. Tolkien and Charles Williams. A scholarly specialist in medieval literature who became best known as a writer of the Narnia books for children. A confirmed bachelor who married a Jewish divorcée from Brooklyn at the age of 58, mainly to allow her to stay in England, only to fall in love and have four sweet years together before she died of cancer.

Mere Christianity came about when the BBC hired Lewis to explain the basics of Christianity to a nation reeling from nightly assaults by German bombers. Much of civilization seemed in peril, with Europe controlled by Stalin in the east and Hitler in the west. Could God truly be in control of human history? Could the forces of good possibly hold out against the forces of evil? Was there any hope?

Here we are in 2015, some seven decades later. Nazism fell and Communism collapsed in much of the world—though not in China, the most populous country. We face different threats today. Disillusioned, most of Europe has abandoned its historic faith. The church wavers in the United States, with one-third of the millennial generation claiming no religious affiliation and the broader culture moving away from its Christian roots. Radical Islam is resurgent, as violent groups like ISIS vow to capture not just the Middle East but all of Europe as well. Most Christian growth occurs in places like Africa and, against all odds, Communist China.

Other defenders of the faith—apologists they’re called—have arisen since C. S. Lewis, but none has the continuing impact of the eccentric don who rarely traveled, never learned to drive, and yet somehow expressed his beliefs so clearly and winsomely that millions still turn to him for guidance. Some fifty of his books remain in print, with total sales exceeding a hundred million. “Name another author whose books are being sold more now than they were when they were alive,” says HarperOne’s Mickey Maudlin. “His vision for the Christian life is seemingly simple while being very complex.”

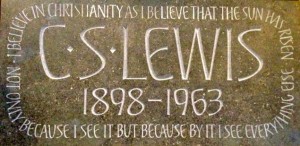

In 2013, on the 50th anniversary of his death—which, incidentally, occurred the same day President John F. Kennedy was assassinated—Lewis joined some of Britain’s greatest writers to be recognized at Poets’ Corner, in Westminster Abbey.

In 2013, on the 50th anniversary of his death—which, incidentally, occurred the same day President John F. Kennedy was assassinated—Lewis joined some of Britain’s greatest writers to be recognized at Poets’ Corner, in Westminster Abbey.

As I recall, I read Lewis’s space trilogy first. Though perhaps not his best work, it had an undermining effect on me. He made the supernatural so believable that I could not help wondering, What if it’s really true? What if there is a God and an afterlife and what if supernatural forces really are operating behind the scenes on this planet and in my life? The tremors strengthened into an earthquake as I went on to read Mere Christianity and The Problem of Pain, which dismantled my defenses and convicted me of the sin of pride.

I was attending college in the late 1960s, just a few years after Lewis’s death in 1963. I ordered more of his books from second-hand bookshops in England because many had not yet made it across the Atlantic. I wrestled with them as with a debate opponent and reluctantly felt myself drawn, as Lewis himself had, kicking and screaming all the way into the kingdom of God. Since then he has been a constant companion, a kind of shadow mentor who sits beside me urging me to improve my writing style, my thinking, my vision. Before writing any book, first I laboriously go through all of Lewis’s to see what he said about the topic.

“If a man will begin with certainties, he will end in doubts; but if he is content to begin with doubts, he will end in certainties,” wrote Francis Bacon, a principle that does not always apply. In Lewis’s case it did: his background of atheism and doubt gave him a lifelong understanding of and compassion for skeptical readers. He had engaged in a gallant tug of war with God, only to find that the God on the other end of the rope was entirely different from what he had imagined. Likewise, I had to overcome an image of God badly marred by an angry and legalistic church. I fought hard against a cosmic bully only to discover a God of grace and mercy.

Lewis affirmed my calling as a writer. We live lonely lives, those of us who make a living by playing with words. I find it hard to write if someone shares the same room with me. More, any impact I have on others will be vicarious. When I write, I am not actively caring for the poor, ministering to AIDS victims, feeding the hungry, or even conversing about spiritual matters.

“We read to know that we are not alone,” said one of the students portrayed in Shadowlands, a movie based on C. S. Lewis. Yes, and we write in desperate hope that we are not alone. Lewis proved to me that this most lonely act can make a difference. As one who was changed—literally, dramatically, permanently—by an Oxford don who felt more at home with books than people, I have learned to trust that God can use my own feeble efforts to connect with readers out there somewhere, most of whom I will never meet.

I doubt C. S. Lewis ever anticipated that half a century after his death several million people each year would buy one of his books, and that Hollywood would release movies based on Narnia with spin-off products available in every shopping mall. If informed of that fact during his life, he would likely have shrunk back in alarm.

We humans are not Nouns, he used to say. We are “mere adjectives,” pointing to the great Noun of truth. Lewis did that, faithfully and masterfully, and because he did so many thousands have come to know and love that Noun. Including me.

Leave a Comment