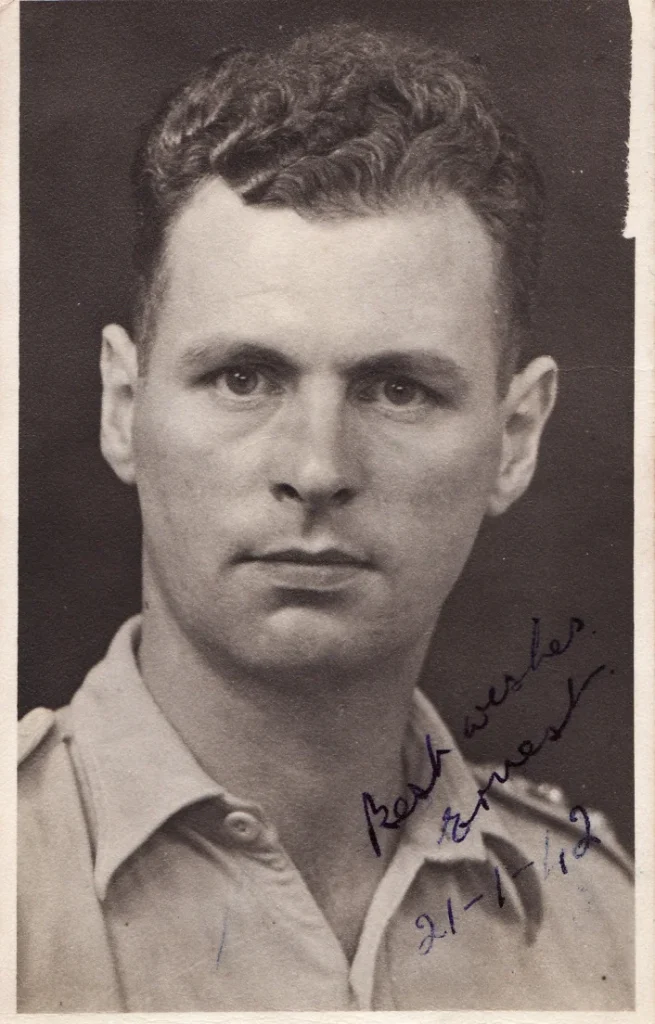

The classic movie starring Alec Guinness, The Bridge on the River Kwai, depicts life in a Japanese prison camp during World War II. This 1957 movie was fictional, but the more recent movie To End All Wars tells the true story of Ernest Gordon, a British Army captain captured at sea by the Japanese at the age of twenty-four.

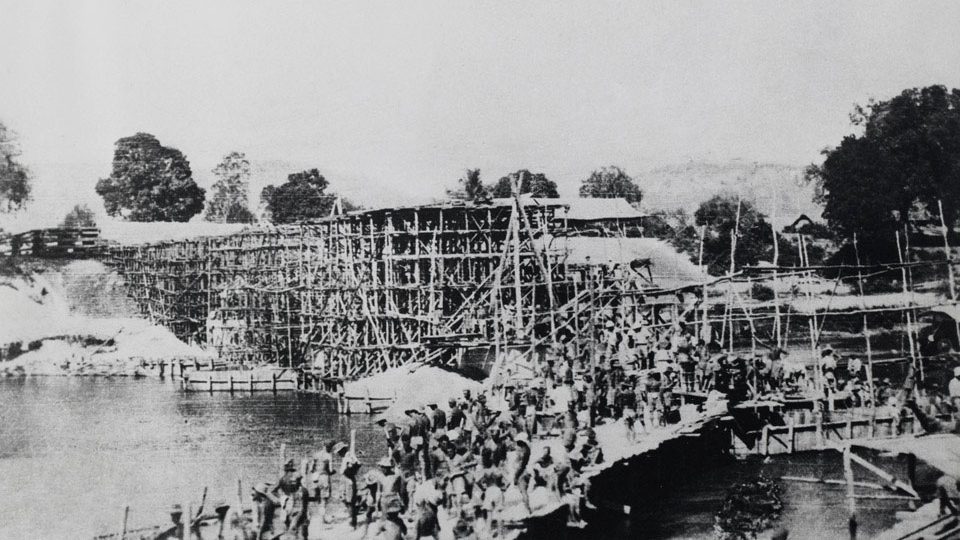

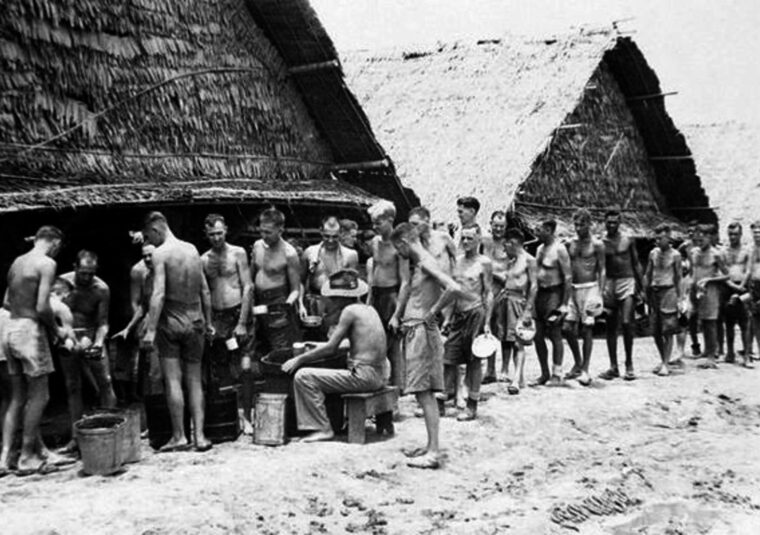

Gordon was sent to work on a railway line which the Japanese were building through the dense Thai jungle. For labor, they conscripted prisoners of war they had captured from occupied countries in Asia, and from the British Army itself. Against international law, the Japanese forced even officers to work at manual labor, and each day Gordon would join a work detail of thousands of prisoners who hacked their way through the jungle and built up a 261-mile track bed through swampland.

The scene was straight out of Dante’s Inferno. Naked except for G-strings, the men worked under a broiling sun in 120-degree (F) heat (49°C), their bodies stung by insects, their bare feet cut and bruised by sharp stones. Death was commonplace. If a prisoner appeared to be lagging, a Japanese guard would beat him to death, bayonet him, or decapitate him in full view of the other prisoners. Many more men simply dropped dead from exhaustion, malnutrition, and disease. Under these severe conditions, 80,000 men ultimately died building the railway.

Ernest Gordon could feel himself gradually wasting away from a combination of beriberi, worms, malaria, dysentery, and typhoid. A virulent case of diphtheria had ravaged his throat and palate so severely that when he tried to eat or drink, the rice or water would come gushing out through his nose.

Paralyzed and unable to eat, Gordon asked to be laid in the Death House, where prisoners on the verge of death were laid out in rows on the ground until they stopped breathing. The stench was unbearable. He had no energy even to fight off the bedbugs, lice, and swarming flies. He propped himself up on one elbow long enough to write a final letter to his parents, and then lay back to await the inevitable.

Gordon’s friends, however, had other plans. They carried his shriveled body on a stretcher from the contaminated earth floor of the Death House to a new bed of split bamboo, installing him in clean quarters for the first time in months.

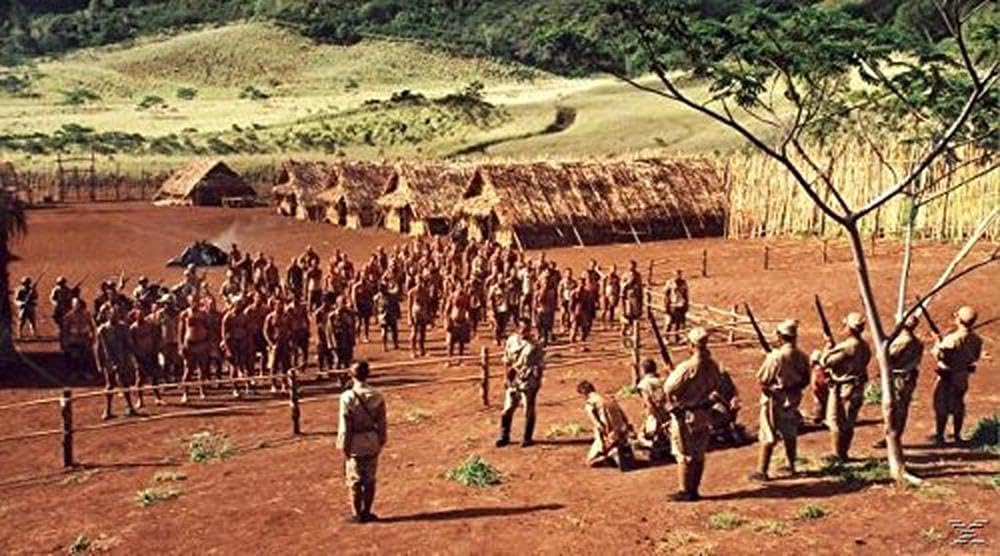

Something was astir in the prison camp, something that Gordon would call “Miracle on the River Kwai.” For most of the war, the prison camp had been a laboratory of survival of the fittest. In the food line, prisoners fought over the few scraps of vegetables or grains of rice floating in the greasy broth. Officers refused to share their special rations. In the barracks, theft was common. Men lived like animals and, for many, hate was the main motivation to stay alive.

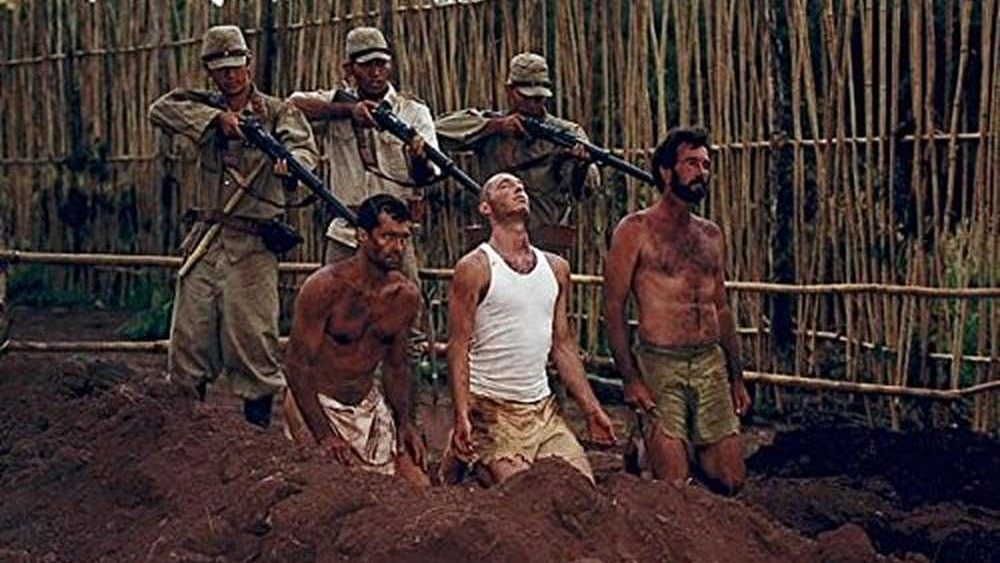

Recently, though, a change had come. One event in particular unnerved the prisoners. Japanese guards carefully counted tools at the end of a day’s work, and one day the guard shouted that a shovel was missing. He walked up and down the ranks demanding to know who had stolen it. When no one confessed, he screamed “All die! All die!” and raised his rifle to fire at the first man in the line. At that instant an enlisted man stepped forward, stood at attention, and said, “I did it.”

The guard fell on him in a fury, kicking and beating the prisoner, who despite the blows still managed to stand at attention. Enraged, the guard lifted his weapon high in the air and brought the rifle butt down on the soldier’s skull. The man sank in a heap to the ground, but the guard continued to kick his motionless body. When the assault finally stopped, the other prisoners picked up their comrade’s corpse and marched back to the camp. That evening, when tools were inventoried again, the work crew discovered a mistake had been made: No shovel was missing.

One of the prisoners remembered the verse, “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” Attitudes in the camp began to shift. Prisoners started treating the dying with respect, organizing proper funerals and burials, marking each man’s grave with a cross. With no prompting, prisoners began looking out for each other rather than themselves. Thefts grew increasingly rare.

Gordon sensed the change in a very personal way as two fellow Scots volunteered to come each day and care for him. One faithfully dressed the ulcers on his legs and massaged the useless, atrophied muscles. Another brought him food, and cleaned his latrine. Yet another prisoner exchanged his own watch for some medicine that might help the infection and fever. After weeks of such tender care, Gordon put on a little weight and, to his amazement, regained partial use of his legs.

The new spirit continued to spread through the camp:

Death was still with us—no doubt about that. But we were slowly being freed from its destructive grip. We were seeing for ourselves the sharp contrast between the forces that made for life and those that made for death. Selfishness, hatred, envy, jealousy, greed, self-indulgence, laziness and pride were all anti-life. Love, heroism, self-sacrifice, sympathy, mercy, integrity and creative faith, on the other hand, were the essence of life, turning mere existence into living in its truest sense. These were the gifts of God to men.…

True, there was hatred. But there was also love. There was death. But there was also life. God had not left us. He was with us, calling us to live the divine life in fellowship.

As Gordon continued to recover, some of the men, knowing he had studied philosophy, asked him to lead a discussion group on ethics. The conversations kept circling around the issue of how to prepare for death, the most urgent question of the camp. Seeking answers, Gordon returned to fragments of faith recalled from his childhood. He had thought little about God for years, but as he would later put it, “Faith thrives when there is no hope but God.” By default, Gordon became the unofficial camp chaplain. A church was organized, and each evening prisoners gathered to say prayers for those with greatest needs.

The discussion group proved so popular that a “jungle university” began to form. Whoever had expertise in a certain field would teach a course to other students. The university soon offered courses in history, philosophy, economics, mathematics, natural sciences, and nine languages, including Latin, Greek, Russian, and Sanskrit. Professors wrote their own textbooks as they went along, on whatever scraps of paper they could find.

Prisoners with artistic talent salvaged bits of charcoal from cooking fires, pounded rocks to make their own paints, and managed to produce enough artwork to mount an exhibition. Two botanists oversaw a garden, specializing in medicinal plants. A few prisoners had smuggled in string instruments, other musicians carved woodwinds out of bamboo, and before long an orchestra formed. One man blessed with a photographic memory could write out the complete scores of symphonies from composers like Beethoven and Schubert, and soon the camp was staging orchestra concerts, ballets, and musical theater performances.

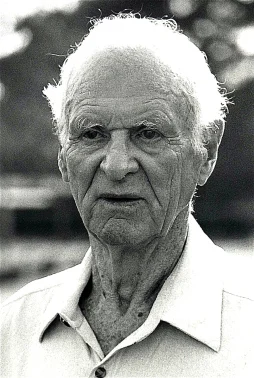

Gordon’s book, Miracle on the River Kwai, tells of the transformation of individual men in the camp, a transformation so complete that when liberation finally came the prisoners treated their sadistic guards with kindness and not revenge. Gordon’s own life took an unexpected turn. In an about-face from all his previous plans, he enrolled in seminary and became a Presbyterian minister, ending up as Dean of the Chapel at Princeton University, where he died in early 2002, just before the movie about his life was completed.

Two worlds lived side by side in the jungles of Thailand in the early 1940s. The miracle on the River Kwai was no less than the creation of an alternate community, a tiny settlement of the kingdom of God taking root in the least likely soil, a spiritual fellowship that somehow proved more substantial and more real than the world of death and despair all around.

To a man, the prisoners clung to the desperate hope that their life would not end in a jungle prison in Thailand but would resume, after liberation, back in the hills of Scotland or on the streets of London or wherever they called home. Yet, even if it did not, they would endeavor to build a community of faith, beauty, and compassion, nourishing souls even in a place that destroyed bodies.

Perhaps something like this was what Jesus had in mind as he turned again and again to his favorite topic: the kingdom of God. In the soil of this violent, disordered world, an alternate community may germinate and flourish. It lives in hope of a day of liberation. In the meantime, it aligns itself with another world, not just spreading rumors but planting actual settlements of that coming reign.

Adapted from Rumors of Another World

Leave a Comment