Unlike most people, I do not feel much Dickensian nostalgia at Christmastime. The holiday fell just a few days after my father died early in my childhood, and all my memories of the season are darkened by the shadow of that sadness. For this reason, perhaps, I am rarely stirred by the sight of manger scenes and tinseled trees. Yet, more and more, Christmas has enlarged in meaning for me, primarily as an answer to my doubts, as evidence of the Creator who exults in life and beauty.

Unlike most people, I do not feel much Dickensian nostalgia at Christmastime. The holiday fell just a few days after my father died early in my childhood, and all my memories of the season are darkened by the shadow of that sadness. For this reason, perhaps, I am rarely stirred by the sight of manger scenes and tinseled trees. Yet, more and more, Christmas has enlarged in meaning for me, primarily as an answer to my doubts, as evidence of the Creator who exults in life and beauty.

In Christmas, the material world and the invisible world come together. If you read the Bible alongside a Civilization 101 textbook, you will see how seldom that happens. The textbook dwells on the glories of ancient Egypt and the pyramids; the book of Exodus mentions the names of two Hebrew midwives but neglects to identify the pharaoh. The textbook honors the contributions from Greece and Rome; the Bible contains a few scant references, mostly negative, and treats great civilizations as mere background static for God’s work among the Jews.

Yet on Jesus the two books agree. And with each online calendar reminder, the flashing date implicitly acknowledges what the Gospels and the history books both affirm: whatever you may believe about it, the birth of Jesus was so important that it split history into two parts. Everything that has ever happened on this planet falls into a category of before Christ or after Christ.

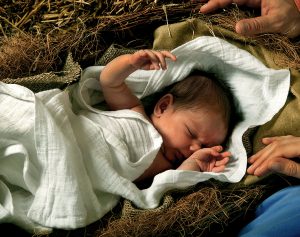

In the cold, in the dark, among the wrinkled hills of Bethlehem, God who knows no before or after, entered time and space. One who knows no boundaries at all took them on: the shocking confines of a baby’s skin, the ominous restraints of mortality. “He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn over all creation,” an apostle would later say; “He is before all things, and in him all things hold together.” (Col. 1:15, 17) But the few eyewitnesses on Christmas night saw none of that. They saw an infant struggling to work never-before-used lungs.

Why did Jesus come to earth? Theologians tend to answer that question from the human perspective: He came to show us what God is like, to show us what a human being should be like, to lay down his life as a sacrifice. I cannot help thinking, though, that Incarnation had meaning in other, cosmic ways.

God loves matter. You can read God’s signature everywhere: rocks that crack open to reveal delicate crystals, the clouds swirling around Venus, the fecundity of the oceans (home to 90 percent of all living things). Clearly, according to Genesis, the act of creation gave God pleasure.

Yet creation also introduced a gulf between God and humans, a gulf that can be sensed all through the Old Testament. Moses, David, Jeremiah, and others who boldly wrestled with the Almighty, flung this accusation to the heavens: “Lord, you don’t know what it’s like down here!” Job was most blunt: “Do you have eyes of flesh? Do you see as a mortal sees?” (Job 10: 4-5)

They had a point, a point God underscored with the decision to visit planet Earth. Choosing words that astonish, the author of Hebrews reflects on Jesus’ life as a time when he “learned obedience,” “was made perfect,” and became a “sympathetic” high priest. There is only one way to learn sympathy, as signified by the Greek roots of the word sym pathos, “to feel or suffer with.”

Of the many reasons for Incarnation, surely one was to answer Job’s accusation. Do you have eyes of flesh? Yes, indeed.

I, a citizen of the visible world, know well the struggle involved in clinging to belief in another, invisible world. Christmas turns the tables and hints at the struggle involved when the Lord of both worlds descends to live by the rules of the one.

In Bethlehem, the two worlds came together, realigned; what Jesus went on to accomplish on planet Earth made it possible for God someday to resolve all disharmonies in both worlds. No wonder a choir of angels broke out in spontaneous song, disturbing not only a few shepherds but the entire universe.

Adapted from Finding God in Unexpected Places

Subscribe to Philip’s monthly blog:

Leave a Comment